21 days of lockdown gives one time to get to things that you keep on putting on the back burner as we rush through our ridiculously busy lives. I have a collection of motorcycle magazines going back to 1970, which I on occasion dig out and browse through. I read an article in a 1995 Cycle World which got me thinking. If you have a sporting bent, chances are you enjoy motorcycle racing. MotoGP, World Superbike or maybe you are a weekend warrior at regional level. I came across a couple of articles on a bike which, in my opinion, took Grand Prix motorcycle racing into another era.

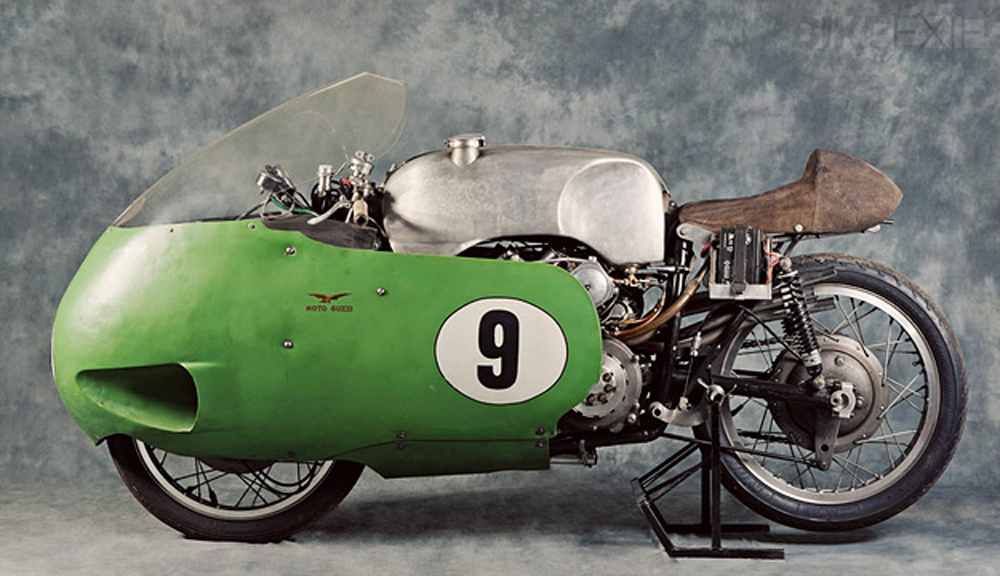

Prior to World War two, there were some really interesting race bikes being built, a few of which utilised superchargers to bump their power considerably. BMW had a “blown” Boxer which was silly fast for the time. After the war, blowers were banned, and engine development took a different direction. Bikes like the Manx Norton, built as a 350cc and 500cc, used single cylinder, double overhead cam engines with 4-speed gearboxes and in 500 form were good for 130 mph. Using the McCandless developed “featherbed” frame in latter years, they were known for their excellent handling and rideability. Another bike worth mentioning, which was dominant and extremely fast in the two years that it was raced, was Moto Guzzi’s incredible 500cc V8. It is best remembered for it’s “dustbin” fairing which was very aerodynamic and helped the bike run to an incredible, for the time, 275 kph top speed. It made 78hp at a lofty 12000rpm and weighed a mere 148 kg’s dry. It was so dominant that it was banned due to its use of a V8 and fully enclosed fairing.

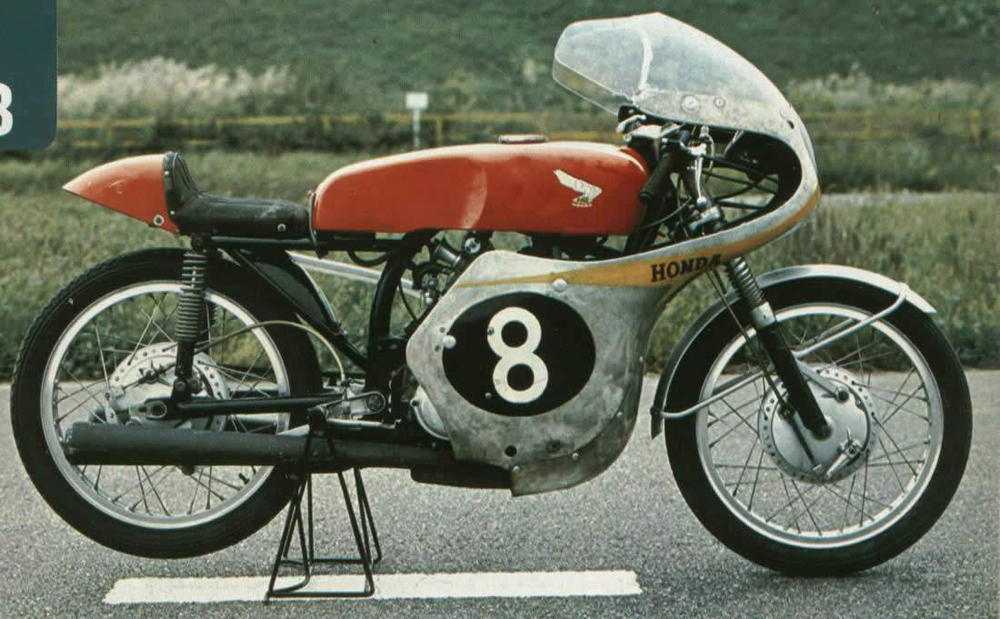

In 1959 a real oddity pitched up at the Isle of Mann with a weird twin-cylinder 125cc bike with leading link front suspension. It was made by a little known company from Japan called Honda. It was the laughing stock of the paddock despite finishing 6th, 7th and 8th but the Japanese looked and learned. A scant two years later, a fellow by the name of Mike Hailwood, raced a Honda RC145 125cc parallel-twin Honda to victory in the 125cc class, ahead of Luigi Taveri on another Honda. This bike made 24hp at, get this, 20,500rpm! Honda did not copy what the Europeans were doing, but marched to their own drumbeat, building reliable, four-stroke, multi-cylinder engines that began to dominate world motorcycle racing. A 250cc four soon joined the fray with great success.

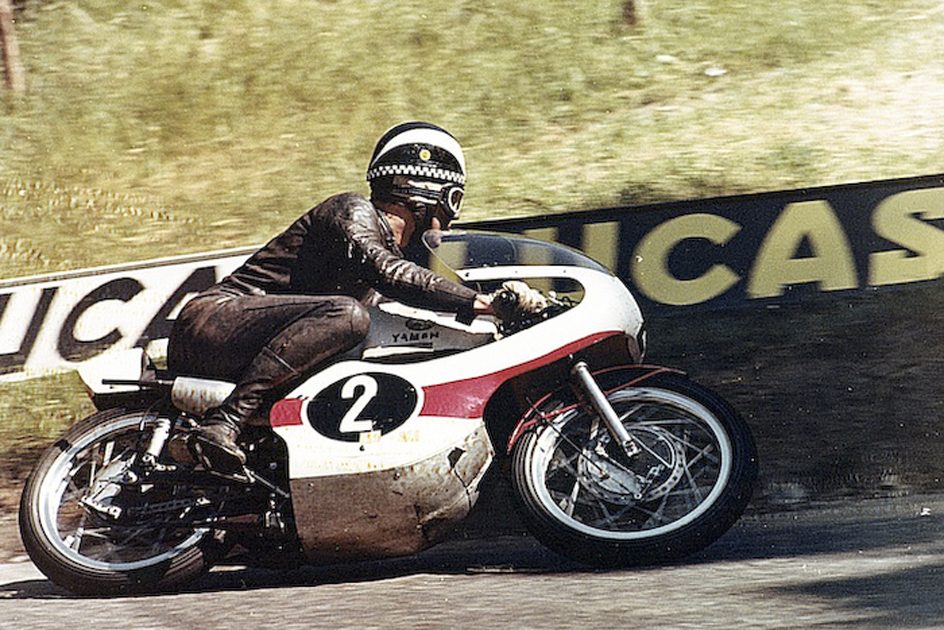

As the sixties moved into the second half of the decade, Honda was experiencing a growing threat from another Japanese company with crossed tuning forks as their logo – Yamaha. In the hands of Phil Read, they started to break Honda’s domination. It was not Honda’s way to try and develop their 4 cylinder bike further. Their response stunned the world. Honda arrived at the Italian GP at Monza in 1964 with a six-cylinder 250! The bike did not have the greatest debut, overheating and being forced to retire, however, it served notice. It was blisteringly quick!

1965 saw Phil Read on his Yamaha narrowly win the championship from Honda, who won both the 500cc and 350c championships. 1966 was a whole new story. Honda, with Mike Hailwood in the saddle, won 10 races to annihilate Yamaha and everyone else. The six’s dominance was complete in both the 250cc championship with their RC166 as well as in the 350cc class with the 297Ccc RC174. At the end of 1967, Honda, with nothing left to prove quit GP racing.

To say that the Honda six’s were mechanical marvels is truly an understatement! You have to see it in the light of 1950’s/60’s thinking. Western engineers scoffed at the four-valve heads. Their flow bench testing had proven that two-valve heads flowed better, but this was at the revs that their singles were capable of, around 7,400rpm. Honda, on the other hand, found that smaller, lighter valves would allow much higher revs before catastrophic valve float or “bounce”, the point where the valve went out of control, simply bouncing on their springs. The same thinking applied to pistons. Multiple cylinders with small, light pistons in a short-stroke engine would give the combustion chamber volume to make superior power, and be able to rev into the stratosphere reliably.

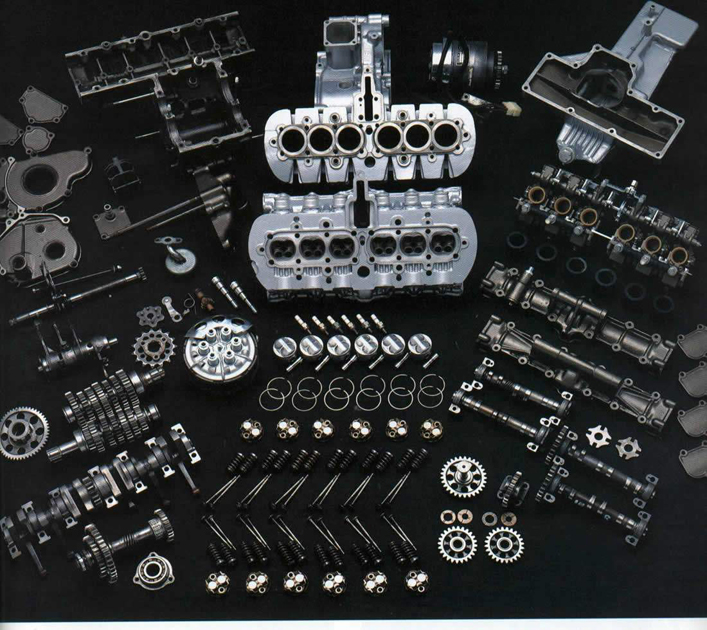

The Honda motors were unbelievable feats of engineering, even by today’s standards. The 250 six made the same specific horsepower [in relation to its cc] as Honda’s RC211V Moto GP bike. How incredible is that? In 1965? The four-cylinder 250 that it replaced was making 45 horsepower at 14,500rpm. The six pumped out 54hp at 19,000rpm. Almost 25% more power. 1964 research on test engines saw them revving to 27,000rpm reliably! The design was almost simple but the attention to detail was otherworldly. The crankshaft was pressed together from 13 domino sized components, with an accuracy of 0.01 of a degree. This is likened to trying to balance 13 billiard balls on top of each other. Unsupported, the crankshaft is so flimsy it can be deformed by hand, yet when bolted in place it is capable of reliably revving off the charts. It rode on odd-sized roller bearings, each designed to scrape oil off the rollers to reduce friction yet provide enough lubrication. The upper engine case and cylinder block were made from one casting to which the main bearings are suspended. This is to allow the lower engine case to be made from a lighter material.

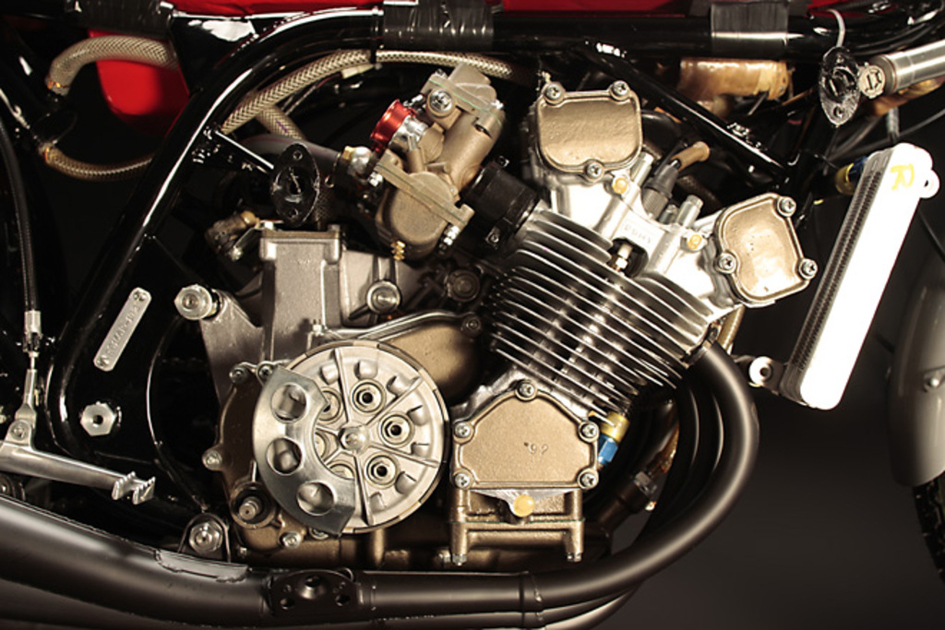

The fully assembled motor was so light that technicians not familiar with the design suspected, upon picking it up, that it was “empty”. The two-piece camshafts joined with an Oldham Coupling, are driven by gears in the middle of the motor. This technology was replicated years later when Honda built the CBX 1000. Not surprising, considering that both projects, the racing six and the CBX, were headed up by the same engineer, Soichiro Irimajiri. The sump is finned, jutting out just below the fairing in the air stream. This, together with two oil coolers, solved the early overheating issues.

Honda also moved away from convention by using different carburettors at different circuits. Round slide Keihins at tight circuits and flat slides at longer circuits. Exhausts were six individual 26-inch megaphones, making the sixes look and sound spectacular. The bike is indescribably loud and revs with an urgency that is absolutely mind-boggling. The engine has no flywheel effect to speak of, with revs rising and falling effortlessly. There were alloys and hardening treatments used in and on motor components that were generally unknown to modern science of that era and even today. Conrods have progressively bigger bearings towards the centre of the engine where the load is greatest. By doing this Honda could make the rods lighter allowing more and faster revving. Main bearings vary from 24mm in diameter at the centre to 14mm on the outside. A replica of the engine was built by a French engineering company JPX, who with the very latest computer-controlled technology took seven weeks just to set up their CNC machines to machine the sand-cast engine cases. How Honda did that in the sixties, no one knows.

The cases are riddled with tiny passages and oilways, some only 1mm apart. The pistons are machined from solid and have only one compression and one oil ring, again to keep friction to a minimum. What this bike cost Honda to build is unfathomable. Mike Hailwood sang the bike’s praises, saying that he could win on this bike “with one hand tied behind my back”. He took on the two strokes and beat them at their own game, fair and square, due to the ease with which the Honda could be ridden, it’s sheer speed and reliability.

The limiting factor of the bikes of this era was the chassis, suspension and tires. The RC’s used the engine as a stressed member, again like the CBX was to do in later years. The frame bolted to the motor and the swingarm to the gearbox. The biggest strides over the years have come in the chassis and tyre department. Electronics are obviously the other exponential growth area. Now that I think about it perhaps nothing has really changed. It took a rare talent like Hailwood to tame the beasts back then. Today there is a fellow named Marques doing the same thing. The six-cylinder bikes that Honda built in the sixties harnessed technology and design features that are spectacular by today’s standards, let alone way back then. Big Red never ceases to amaze!