Even if Sunday’s race was a snore-fest, it was still hugely significant. Bastianini did his chances of staying with the factory Ducati squad no harm whatsoever with his dominant victory, helping his teammate’s championship hopes along the way, in the face of rumours that Jorge Martín could potentially be promoted to the factory seat alongside Pecco Bagnaia at Bastianini’s expense in 2024. It would be grossly unfair for Bastianini to lose his seat based on his performances this year as he has been massively compromised by injury and Sunday’s victory showed that he is a talent worth holding onto: let’s not forget his four victories in 2022 on a satellite Ducati, so easily forgotten in the face of a bad following season.

Bagnaia then helped his championship aspirations by beating Martín into fourth place, clawing back some of the points lost to Martín in the Sprint race (Martín 3rd, Bagnaia 4th). Leaving the Far East for the last time this season, a lead of 14 points with two races and 74 points still up for grabs is nothing to be sniffed at. Those are the bare bones but, as usual, if you took the time to delve a bit deeper, there were many stories behind the on-track action.

Not least of the most significant was the post-race low-tyre pressure penalties handed out to several riders, the most important being Bagnaia, putting himself in the same position as Martín, in that one more transgression would result in a three-second penalty, which could have a drastic effect on the championship outcome. It will be disgusting if the championship is decided because of a rule that no one wants, which has only been implemented because of Michelin’s inability to produce a tyre that can withstand the forces being applied to it thanks to the proliferation of aerodynamic downforce aids. Or maybe the aerodynamic aids are to blame for putting too much pressure on the tyre? It is not for me to decide which view has more accuracy.

There are some worrying trends in MotoGP at the moment, where it appears that decisions are being made without due consultation with the riders who are, after all, the ones putting their lives on the line every race weekend – now more than ever with the Sprint races effectively doubling the risk. The pressure on team personnel is also huge and the steadily increasing calendar will only exacerbate that. It’s a consequence of commercialisation, of course, but would we rather have a season of full grids every race or, as we have had this season, barely one race that has had a full grid of full-time riders? We got along very well without Sprint races for a long time and we all love them as it doubles our enjoyment every race weekend but is it worth it, if the championship is affected?

In effect, you are asking riders to compete in and complete two full seasons’ worth of racing in one season. Forget that the Sprint races are half-distance: the riders try no less hard because of it and the risks are exactly the same, but injury in a Sprint race has a bigger impact on the season as a whole because you have compromised your season for a smaller number of (potential) points.

Now you are telling riders that they have to run with a front tyre far too hard for effective grip when riding on the limit, which all these riders do every single lap. When a championship starts to encourage teams to have permanent reserve riders to take up the slack if the full-time riders are injured, then you know that things have gone too far.

The teams aren’t entirely blameless: the aerodynamic path down which they have all been forced to tread in order to keep up with each other could have been nipped in the bud early on but such were the performance gains, for which every team fights so hard, that they were extremely attractive. The same goes for the ride height mechanisms.

Now, I’m all for progress and I understand that MotoGP, like Formula 1, is the pinnacle of motorsport and should be a no-holds-barred contest, with the best engineering minds pitting their wits against the laws of physics and the rule book. To artificially rein in the technical progress of MotoGP would be to make it no better than production-based World Superbike racing but there comes a point where the so-called progress actually does more harm than good and we are at that point now, especially with regard to aerodynamic efficiency which have been proven to ruin racing in almost any category you’d care to mention where it has proliferated.

Should we really be cautious about giving too free a rein to the manufacturers or teams, as happened in the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s, or would it promote fascinating and possibly beneficial technical progress? Imagine if standard bodywork was mandated but the concession would be greater mechanical engineering freedom: would that work? Of course, the wealthier teams would always have an advantage and you’ll always run the risk of one team running away with every race and the championship but then perhaps a young and gifted designer could come to the fore with new ideas: remember Gordon Murray in Formula 1 with Brabham? All sorts of fascinating technical ideas that stretched the rule book wafer thin and were just on the right side of legality. The same with Colin Chapman of Lotus and their modern (and for the last 35 years…!) equal: Adrian Newey? Wasn’t racing all the more interesting for their input?

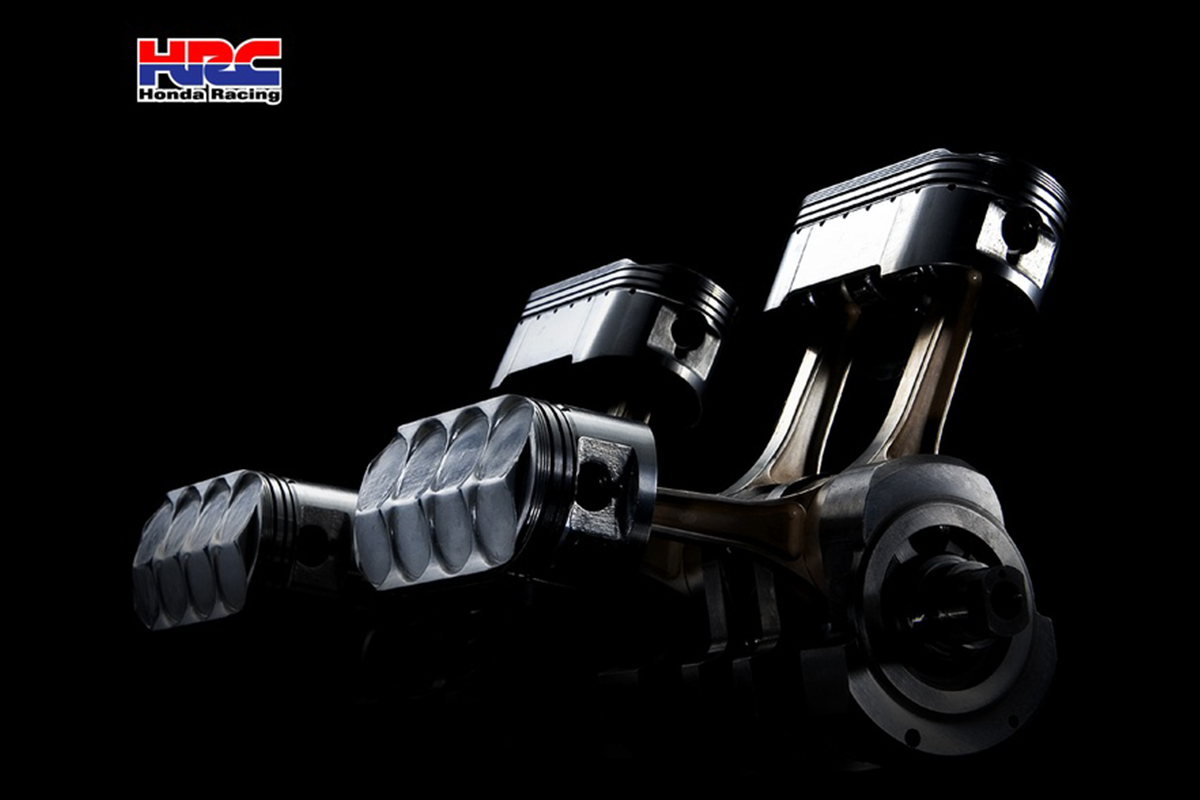

In the 1960s, technical progress in motorcycle Grand Prix racing was incredible, as was the engineering, and the Japanese factories pulled no punches and had seemingly bottomless cash pits. While Yamaha and Suzuki concentrated on two-stroke technology, Honda was determined to stick to four-strokes, which company founder Soichiro Honda felt had more relevance to road-going motorcycles.

However, for a four-stroke engine to match a two-stroke in terms of power for a given engine displacement, it has to have roughly twice the number of cylinders. This gave rise to the unprecedented sights – and sounds! – of Honda twin-cylinder 50 cc, four- and five-cylinder 125 cc and four- and six-cylinder 250 cc and 350 cc engines from the early to mid-1960s, all with stratospheric rpm limits and anything up to a dozen gears to compensate for the relative lack of torque: just astonishing, and it couldn’t last because the development costs were just too high. The F.I.M eventually stepped in and mandated the number of cylinders permitted for each class: the technical war had prevented anyone else from getting a look-in and it was killing the sport. Restrictions at that time helped save the sport, even if the four-stroke MV Agusta was dominant in the 350 cc and 500 cc classes for so long before the two-stroke Yamahas and Suzukis took over.

Honda left racing at the end of the 1967 season, with nothing left to prove having won everything, and revolutionised road motorcycling with the 1969 CB750. When Honda returned to racing in the early 1980s, the philosophy went against contemporary Grand Prix motorcycle design, which was completely dominated by two-stroke engines. The result was the frankly preposterous four-stroke NR, with its V8-turned-into-a-V4 engine, through the use of oval pistons that adhered to the letter of the law in that a 500 cc engine could only have four combustion chambers. Thus, each pair of combustion chambers of the Honda V8 comprised two cylinders with no cylinder wall between them, hence the oval piston. It had 32 valves and two conrods per piston. And was still only 500 cc, remember!

As a racing motorcycle, it was an abject failure but it was an incredible technical achievement and it says so much for Honda that the company would relent, re-group and re-energise itself and its two-stroke engines would dominate the sport for the next 12 or so years.

The rule book is there to not only inspire new engineering solutions (at the commencement of a new set of rules) and to preserve safety limits but also to shake up the engineering and design challenge every now and then. No one will ever say that safety isn’t the most important element of any racing series, but the minimum tyre-pressure rule is misguided and is going to kill the sport dead. This year there is a penalty system: first offence; a warning. Second offence a three-second penalty applied retrospectively, then a six-second penalty for a third transgression. Next year, it will be disqualification from the results for any transgression, with no questions and no leeway. It’s madness and, far from promoting safety, it actually makes things more dangerous as an over-pressure front tyre is an accident waiting for somewhere to happen.

For many years, riders ran under the recommended front tyre pressure with no danger of sanction and the irony is that the minimum pressure rule was introduced because the riders who stuck to the (unenforced) letter of the law were fed up with those who didn’t. Talk about your own goal! That the minimum pressure is now as high as when riders won races with the tyre at full temperature (and, therefore, pressure), is a miscalculation of epic proportions and smacks of Michelin’s legal department getting the jitters about an accident caused by a collapsing tyre due to being run under-pressure (which has never been a concern.) It’s normally called fear of litigation in the event of an accident, but the responsibility for that has now shifted from the tyre manufacturer to the rider, who has no input into the design and construction of the tyre, but who has to try and compete with the product and be blamed if it fails!

It is possible for a rider to start the race under pressure but then he is banking on the pressure rising with the temperature if he is in a pack of riders, and the temperature and pressure will rise and he can’t fight. But, if he is out in front, in clear air, then the gamble will backfire and he’ll be penalised for being under pressure. It’s a no-win situation: damned if you do – damned if you don’t.

It gives me no pleasure to concentrate on the negative sides of a sport that gives us so much pleasure. MotoGP is incredible at the moment and we have to take the rough with the smooth because there is so much more smooth than rough. I’ll take a boring race every now and then if the pay-off is what we’ve got more often than not. But those in charge need to listen to the riders a lot more.

We’ve got two races to savour before the season concludes and they’re going to be nail-biting affairs. Let’s hope that it’s a straight fight on the track and not in the stewards’ room afterwards.