It was the best of times. On a beautiful Wednesday morning, I cruised through the suburbs of Joburg on my BMW R 1250 GS Adventure. I was on my way to collect a BMW R 1300 GS demo from Motorrad, Sandton. It was the worst of times. I overtook a Toyota Cross just as the driver turned right into her driveway. The collision hurled me across the road, and I landed hard on the pavement. It’s been decades since I crashed on tar. I lay winded on the pavement, taking stock of my limbs and, mercifully, I seemed to be OK despite being badly shaken. Kind passersby picked up my GSA, which appeared to have suffered minimal damage and started easily. It could have been an aggravated encounter with the driver, but once we confirmed we were both comprehensively insured, the tension evaporated. The driver and I travelled together to Linden SAPS in her newly battered Toyota to report the accident for insurance claim purposes. After being buggered around at the cop shop for a mere two and a half hours we returned to the scene of the accident, parted ways and I continued my interrupted journey to Sandton.

I collected the sparkling Triple Black 1300 from the friendly Motorrad folk and was loose on the land at noon, having lost three hours of prime riding time. My destination for the day was Bloemfontein, and the path of least resistance would have been to tool down the deathly boring N1, but I had planned a backroads route and there was plenty of time to stick to Plan A. I rode the dreaded M1S and M2E, then followed the R59 south.

In the March 2010 issue of Bike SA Magazine, I wrote an article about two Suzuki Boulevards developed by Trajan TG Grobler, the legendary bike builder. Earlier this year, TG called and asked if I had a copy of the article, so I fished it out and had it in my backpack to give to him. TG operates from his premises in Alrode just off the R59, so it was a minor detour to pop in for a café and a catch-up. TG is the first choice for men who are serious about releasing the hounds of hell that lurk inside every Suzuki motor. All those years ago, when I collected the Boulevards, I recall watching TG complete the assembly of a GSX-R1000 motor. As he torqued the last cylinder head bolt and the torque wrench clicked, he spoke, “That’s perfect, but it will have to do.” As pleasant as the conversation and the coffee were, tempus fugit, and I still had more than 500km to ride to Bloem.

I continued south on the R59, crossed the Vaal and followed the R57 to Heilbron and Lindley. The roads were in good condition, and there was very little traffic. I set cruise control at a leisurely 150km/h and the Beemer and I got into serious distance demolition mode. Just past Petrus Steyn, I turned southwest on the R707 to Lindley, Arlington, Senekal and Marquard. It was a golden afternoon. The GS was running effortlessly like a long pedigreed dog with the engine temp readout constant at 82°C. I sat in a cocoon of still air behind the windscreen, comfortable despite the pain in my left shoulder. Until Marquard, the ride had been easy and stress-free, but that couldn’t last forever.

It’s 30km from Marquard to Clocolan, 30km of diabolical potholed tar where the signs have been annotated to read “Huge Potholes”. I think it would have been appropriate to have signs stating “You Might Die Today”. Eventually, I stopped in Clocolan for fuel. My plan was to ride the deserted platteland road to Excelsior and thence to Tweespruit and the N8. When I told the petrol jockey I was going to ride to Excelsior, he gave an exaggerated eye roll and said, “If you think the Marquard road is bad, the road to Excelsior is ten times worse. Rather ride to Ladybrand and then the N8 to Bloem.” Sage advice. Had I not lost so much time that morning, I would have ridden the backroads, but the shadows were lengthening and my host for the evening was expecting me at 17:00.

I cruised due west past Westminster and Thaba Nchu straight into the malevolent eye of the setting sun. There were cops everywhere, so I rode at the speed limit and reflected on the sights I had seen that day. My enduring memory of that ride through the platteland was the proliferation of shacks on the outskirts of every town. Three metres by three metres zinc dwellings spread like a shiny rash across the bare veld. There’s no shade, no water, no electricity, no sewage system, no roads, no employment, and, I imagine, no hope. It’s just bleak and depressing. I don’t know what the answer is, but exponential population growth is not going to end well.

When planning this trip, I decided to sleep in Bloem on the first night. I’m not a fan of sterile hotel rooms, so I used my network and within an hour I had an invitation from Frans Henning from the Harley-Davidson Club to sleep at his home. I arrived at Frans’s home in Fichardt Park just after 17:00 and, as bikers do, we hit it off like old mates, drank a few beers, and then he drove us to a local bikers’ boozer for a steak dinner. It was a very pleasant evening, but after a tough day, I was keen to rest my aching carcass. I ate a handful of Schedule 5 painkillers and sank into the arms of Morpheus.

On Thursday morning, the bruises on my torso had bloomed into a garden of rainbow shades. Despite the painkillers, I was taking strain. I found a pharmacy, got a Voltaren injection and then rode to the National Women’s Memorial to meet my connecko Johan Colyn, a local historian. The Women’s Memorial is a shrine to the 26000 Boer women and children who died in British concentration camps during the Anglo-Boer War. It is one of Afrikanerdom’s most holy places. The monument was unveiled on 13 December 1913. It comprises a 120-foot-tall obelisk and a statue by Anton van Wouw inspired by Emily Hobhouse.

When Emily Hobhouse was visiting the concentration camp at Springfontein, she encountered a group of dishevelled and neglected women near the station. There was no accommodation available for them in the camp itself because there was a shortage of tents. With sticks and pieces of old canvas which they scrounged from the British soldiers, they had erected rough shelters. Hobhouse was called to attend to a sick child, and she described the following scene: “The mother sat on her little trunk with the child across her knee. She had nothing to give it, and the child was sinking fast. There was nothing to be done and we watched the child draw its last breath in reverent silence. The mother neither moved nor wept. It was her only child. Dry-eyed but deadly white, she sat there motionless, looking not at the child, but far, far away into the depths of grief beyond all tears. A friend stood behind her who called upon Heaven to witness this tragedy, and others crouching on the ground around her wept freely.” The Women’s Memorial is a spiritual place and well worth a visit.

Once Johan and I said our farewells, I rode southwest out of Bloem, stopped for a Big Mac in Fleurdal and then followed the R706, destination Jagersfontein. The R706 is a road you need to ride. It runs dead straight for 110km across seemingly infinite savannahs bereft of any signs of habitation. I set cruise control and relaxed in the saddle, alone and content with my thoughts. In the hour-long ride to Jagersfontein, I saw less than a dozen vehicles. I was an insignificant speck in a vast landscape, a lone voyager navigating an ocean of grass.

Jagersfontein is the site of the largest hand-excavated hole in the world, with a depth of 200 metres and an area of 20 hectares, slightly larger than the Kimberley Big Hole, which is 17 hectares. In 1870, a farmer found a 50-carat diamond in the veld, and a diamond rush ensued. The most famous diamonds found at Jagersfontein were the Excelsior, 972 carats, and the Jubilee, 650 carats, named in honour of the 60th anniversary of Queen Victoria’s coronation. Fifteen years ago, I visited the mine, which was a tourist attraction open to the public, and I wanted to see the hole again. That morning, when I asked Johan about the mine, he said it had been closed for years, even before the calamity which struck the town in 2022. In the early hours of 11 September 2022, the catastrophic failure of the mine tailings dam released 6,000,000m3 of liquid sludge, which smothered 200 houses and 1600 hectares of farmland. De Beers closed the mine in 1972, and since then, the town has been dying by inches. In the aftermath of the collapse of the dam, it’s almost a ghost town with a few tatterdemalion businesses barely surviving on the main street.

The grounds of the mine were enclosed by a two-metre palisade fence. At my age, I had no illusions about being able to scale the fence. However, there was a spot at ground level where it appeared as if someone had forced the fence away from the upright pole. I tugged on the palisades until the gap was big enough to squirm through. I walked across the grounds and squeezed through a narrow steel cage, which was once used to control access to the hole. Instantly, I was in a world of pain. There was a wasp nest about 10cm in diameter in the top corner of the cage from which squadrons of wasps launched themselves and attacked my hands, neck, ears and head. Squealing like a piglet, I beat an undignified retreat. I was stung at least twenty times, but I hadn’t come this far not to reach my goal. I put on my helmet and gloves and zipped my jacket collar up to my chin. Second time around, the wasps were just as agitated, but I made it through unscathed. The fifty-metre boardwalk leading to the hole was completely rotten with two-metre-tall rank weeds growing through the cracks and holes. I trudged through the growth to the cantilever platform, which extends for twenty metres beyond the lip of the hole. The platform seemed to be sound, so I walked to the end and gazed into the abyss and thought deep thoughts for five minutes before returning to the bike. Mission accomplished. A trip to Jagersfontein might not be everyone’s idea of fun, but for me it was a splendid adventure, one which I highly recommend.

Just 12km west of Jagersfontein, I stopped for photos in the main street of Fauresmith. What makes Fauresmith special is that it’s one of only three towns in the world where the railway line runs down the middle of the main street. The other two are Tullahoma, Tennessee, USA and Wycheproof, Victoria, Australia. Unfortunately, the last locomotive chuffed through Fauresmith in 1999. I stopped at the Phoenix Restaurant for a Coke and then rode 50km to Koffiefontein. That town is a disgrace. The main road has more potholes than tar, there’s litter everywhere, and raw sewage runs in the gutters. During WWII, Koffiefontein was an internment camp for Italian POWs. One of the prisoners, an artist named Fascio, painted murals of King Victor Emmanuel III and Benito Mussolini. The murals have been preserved and are still in remarkably good condition. It was a short blitz to Luckhoff, where I stopped for fuel and immediately wished I had not. Before I could remove my helmet, a couple of scaly bliksems were in my face, telling me their tragic life stories and asking for money. A security fellow chased them away. They epitomised a town infested with ragged unemployed people and hordes of scruffy urchins lounging around with nothing to do and all day to do it.

The steel girder Havenga Bridge crosses the Orange River downstream from the Vanderkloof Dam. The Orange is the border between the Free State and the Northern Cape, and it was a short ride to my destination for the day, Orania, the jewel of the Northern Cape. I checked into Die Oewer Hotel, changed out of my riding kit and went exploring. You can read all about Orania on the internet, so this is a list of my observations: I did not see any burglar bars, electric fences or razor wire. There is no litter. The people are polite, helpful, friendly and proud of their town. The thriving industrial area features many specialist engineering workshops. There are thirteen different churches!! The droëwors I bought was the best I’ve ever eaten. There’s only one liquor store in the town. Orchards of mature pecan nut trees are a feature of Orania. The majestic Orange River, wide and deep, was a few metres from my hotel room and is the font of Orania’s thriving agricultural sector. Rain began to fall, and I retired to my room with a couple of cans of beer and my packet of droëwors. After my picnic dinner, I slept a sleep of contentment.

On Friday morning at 09:00, I met Hennie Pelser, one of the very first people to settle in Orania when it was founded in 1991. Hennie is the foremost pecan nut grower in Orania and enjoys taking tourists around town in his three-wheel ELEKTRA. He was a fount of knowledge. There is zero unemployment and no homelessness in Orania. There are more than one hundred houses under construction, with many more planned. This is a haven where Afrikaners celebrate their culture, their community and their language. Good for them. Long may they prosper. I walked up Monument Hill to see the six busts that gaze with steely eyes over the town. To this day, Paul Kruger, JBM Hertzog, DF Malan, JG Strijdom, HF Verwoerd and BJ Vorster are revered as leaders who fought for the rights of Afrikaans people in South Africa. Standing in front of them is a statue of a young boy rolling up his sleeve. He is called “Kleinreus” – Little Giant – and is the can-do symbol of Orania.

From Orania, I rode south, made a detour to Vanderkloof for a photo of the dam wall and then continued south to Petrusville. Looking at the map the previous evening, I saw what looked like a dirt highway running from Petrusville to Colesberg. Just south of town, I found the R369 and rode into the magnificent solitude of the Karoo. The road was in immaculate condition, and I bombed along at 160km/h for the first 10km with great vortices of dust billowing from the rear wheel. But then I backed off. I relaxed at 100km/h and imbibed the immensity of the landscape, the freshness of the morning, the scent of the vegetation and the infinity of the cerulean sky bowl.

Once a year, about forty dodgy old bikers gather for a weekend of gentle debauchery in a platteland dorp. The Poetry Rally was first held in 2000, and every year since then the jol has been a keenly anticipated event. This year, our venue was the Philippolis Hotel, 56km north of Colesberg. On Friday afternoon, the manne rode in from across the country, and that evening there was a riotous party in the hotel bar. Our host for the weekend was Mike, who runs the hotel and who did a splendid job of accommodating the rowdy, hungry and thirsty bikers. After breakfast on Saturday, we had the whole day to explore the hamlet and its environs. Philippolis has developed a deserved reputation as a funky town, home to artists and bohemian refugees from the cities. We strolled the dusty streets, peered into the art galleries, and stopped for golden throat-charming lagers in bars that played excellent music. We rode a few clicks out of town to Route 717 Pub on the banks of the Waterkloof. The microbrewery concocts delicious Karoo Ale made with the crystalline waters from the river on its doorstep. It was a wonderful, serene day, just what I needed, and the bonus was a refreshing afternoon siesta to prepare for the evening ahead. Saturday night cabaret was a trio of local geriatrics called “Die Wilde Toppies”. They were great entertainers and a fitting finale to a memorable weekend.

When I woke on Sunday morning, my shoulder was beyond painful, and I wasn’t looking forward to the 600km ride from Philippolis to Joburg. 600km is not that far, but it’s not trivial either. But I had Willie Nelson to cheer me up as I sang into my helmet on the road north to Trompsburg and Bloemfontein… I stopped in disbelief at the ruins of the Trompsburg railway station. The weed-infested railway tracks are still there, but every building has been smashed to smithereens. What a difference thirty years makes.

On the road again

Goin’ places that I’ve never been

Seein’ things that I may never see again

And I can’t wait to get on the road again

I set cruise control at 140km/h and let the GS do all the work while I tried to find a position that didn’t aggravate my shoulder. In Winburg, I turned off and rode to the Voortrekker monument on the outskirts of town. The razor wire gate was closed but not locked, so I pushed it open and rode to the monument for photos. The grounds are unkempt, the roads are cracking up, and the weeds are taking over. It’s incomprehensible that there’s no sense of heritage or history in SA unless, of course, it’s to do with changing the names of towns. By Kroonstad, I was sick of the N1 and decided to ride the R721 to Vredefort and Parys, a road I had not ridden in many years. It was a warm afternoon, the road was in perfect condition, the GS was effortless, and after a 2000km weekend in the saddle, I was in a happy place. After Parys, I rejoined the N1 and as the shadows lengthened, the Joburg skyline appeared on the horizon.

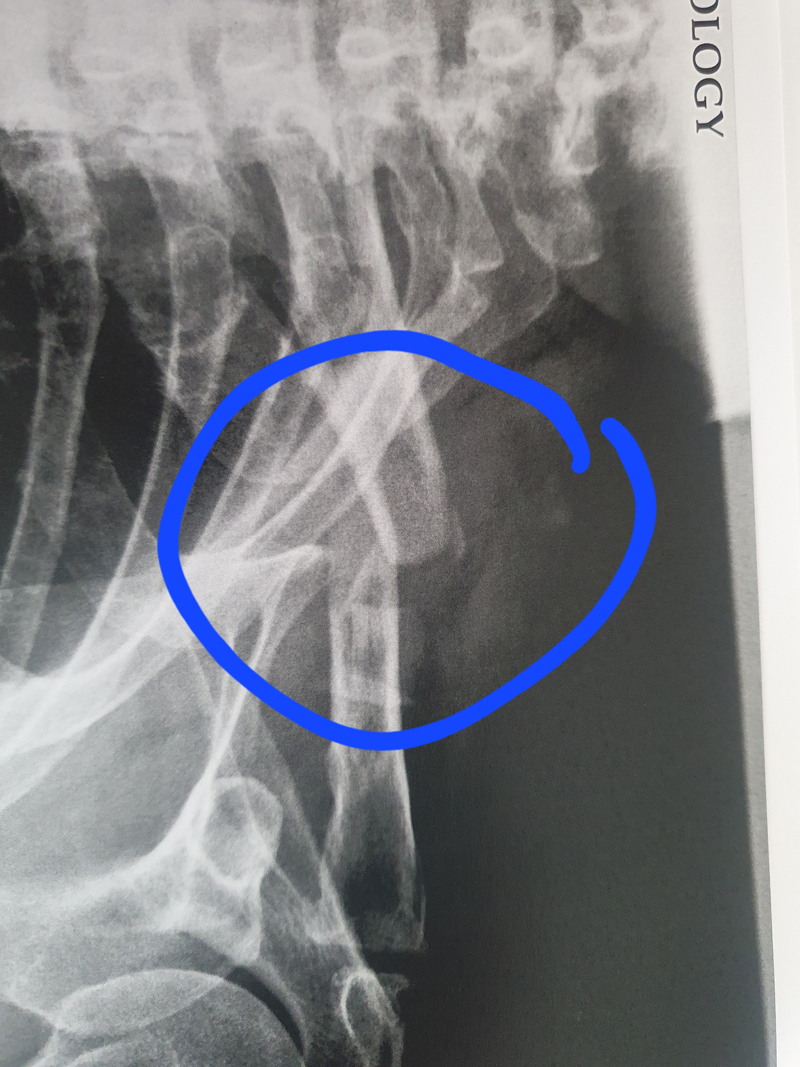

At my daughter’s home, I asked her to help me take off my riding jacket. As she tugged on the left sleeve, I winced as the jacket dragged my shirt over my shoulder. Catherine exclaimed, “Crikey, Dad. You’ve got a bone sticking out of your shoulder.” She was right. I had a displaced fracture of the clavicle, which needed surgery. I suppose the intelligent decision would have been to have the surgery performed in Joburg, but what the hell. I’d already ridden 2000km with a broken bone, and a further 350km home to Nelspruit wasn’t going to make a difference. On Monday morning, I returned the GS to Motorrad, collected my bike, rode home and checked myself into casualty.

In 2024, I rode the 1300 GS on the BMW press launch in Mpumalanga. I loved the GS then, and I loved it even more on the long road. The GS is the benchmark for dual-purpose motorcycles. Small wonder that my R 1300 GS Adventure will be the eighth GS I have owned.